The Story of my Life

Louise Virginia (Weir) Frasier

| Home | Introduction | Preface | Chapters | Do You Remember? | Stuff | Contact |

Chapter VIII

|

W |

hen we got to Tennessee in 1927, the house on the farm wasn’t empty, so we had to live in one in Flintville for a month. After the people moved it took us three weeks to clean and cut the weeds around the house. Now I’ve told you that houses then were not like they are today, but we’d always lived in decent houses. This house wasn’t fit for animals to live in! It was big enough for the times: seven rooms and one of them big enough for four beds—sort of like a bunk house. But terrible! In terrible condition!

Finally, we moved in on Thanksgiving Day. Papa had to go back to Alabama, so he caught the train back. The day after Thanksgiving Mama was still getting organized. I guess there had been an addition for there was a hole for a window by the stove.

Mama said, “I’m not going to have that like that. We need a dining room, so get the saw and cut that wall down to the floor so we can have a door there.”

We were not very well organized and couldn’t find a hand saw. Mama said, “There’s the cross-cut saw, use it.” So me and Buford got the cross-cut saw and cut a door into the room that had been added on.

When we finished Buford said he’d take the saw to the barn and put it where it belonged. I said, “No. Let me. I want to look around.”

There was an eight foot gate across the barn hall. Instead of opening the gate, I put the saw over and leaned it against the gate. Then I climbed to the top of the gate and took a good look around. I jumped down and as I did, I sawed my leg from my knee to my ankle! I had on heavy socks, and at first I thought I’d only sawed my sock. Then I saw the blood spurting everywhere!

About that time Buford yelled, “You’ve cut you leg off!” and grabbed an old sack and tied it around my leg above the knee. We yelled and yelled but nobody heard, so I got on his back and he carried me to the house.

We’d already learned that there was no doctor in Flintville: there was one in Elora, and one in Kelso—each about six miles from Flintville. Buford jumped on the old mare they’d traded Sam for. That’s when we learned you couldn’t ride her. She bucked him off.

Mama was trying to stop the bleeding. Some people we hadn’t met yet came by in a wagon. They came in and wanted to get soot out of the chimney and put it on my leg. Thank goodness, Mama wouldn’t let them do that.

Buford got to Flintville—I don’t know how! And the doctor from Kelso was there in his buggy. He came out. The bleeding finally stopped. He didn’t have a surgical needle, but sewed it up with a regular sewing needle.

Then the doctor said, “When did you folks move in here?” Mama said, “Yesterday.” He said, “I would have moved out today!”

I couldn’t walk on that leg until the end of February.

When Dot was born, that same doctor delivered her. He said, “Who sewed that up?” I said, “You did.” He said, “Why didn’t you sue me? That’s the worst scar I ever saw!”

I witnessed another psychic experience when Dora had double pneumonia. Both Dr. Shelton and Dr. Griffin treated her and said that the pneumonia would run it’s course in nine days. They said that her temperature was so high and she was so sick that they were sure that she wouldn’t live. Someone had to sit by her bed all the time and some of the neighbors came to help out.

Dora was unconscious most of the time. On the ninth night the doctors went home but said that about midnight her fever would break and she might die. Mama was exhausted and said that she was going to lie down for an hour or two. She told me to sit by the bed. Comer and Coy and Ruth Reynalds were there in the room with me. Suddenly, Dora sat up in bed and started laughing and talking. She said, “Look at the butterflies! Look at the kids playing with the lambs!”

I reached over and took her hand. It was ice cold and when I turned it loose it just flopped down on the bed. Before I could call Mama, Dora lay back down and said, “But God, I can’t leave Nora. Take Louise instead.” Ruth Reynolds fainted. I yelled for Mama and the people on the porch came running in. Someone gave Dora some whiskey. The next morning when the Doctors came, she was cool and on her way to recovery.

Another story about doctoring: a story too nasty to write about but true. After Dora got over pneumonia, George William got bad sick. The doctor said he had pneumonia and started doctoring him. We sat up with him. About the fourth day, Mama was so tired that I said I’d stay out of school so she could rest.

Mama was sleeping and I was rocking George William in front of the fire when he started choking. I screamed and Mama came running. Then those big long stomach worms started coming out of his nose and mouth! Mama grabbed handfuls, handfuls! He finally stopped checking and Mama told me to go to Flintville and see if I could get a doctor.

Luckily, I found him in Flintville, again, and I told him what had happened. He said, “Damn, I ain’t got no sense! I should have thought of that with that swollen stomach and those red cheeks.”

He went into the store and bought a bottle of Dr. Galt’s dead shot worm oil. I got in the buggy and we went back to the house. The doctor made George drink all of that and told Mama to watch his stool. George passed a hundred and seven more of those worms!

Once, when George William was about three years old, he was playing at the wood pile. I was near by reading. Suddenly George screamed out. I thought he’d been bitten by a snake or something. But he said, “Oh, I was just telling myself a bear story and got scared!”

|

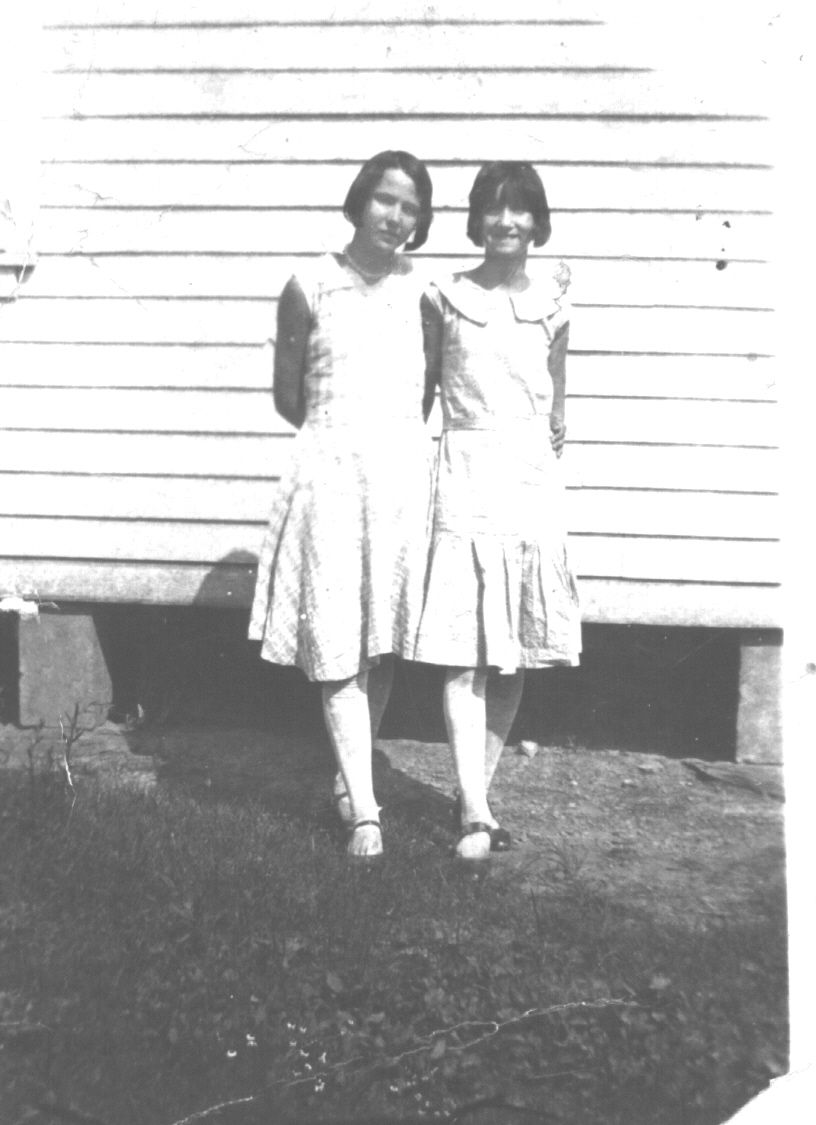

Louise and Mary Will |

When the twins started to school, George was the only kid left at home, and he and the twin’s dog, Ted, were very sad. As we started walking to school, George would sit on the porch with an old straw hat on, and Ted would sit beside him. George would cry, “Boo hoo!”, and Ted would howl. George would cry, “Boo hoo!”, and Ted would howl. Finally, George quit crying and turned to Ted and said, “Shut up!”

The twins were iden-tical. Mama always dressed them alike and they insisted on dressing alike. One morning, we had walked almost to school when Nora noticed that they had on different socks. They raised such a fuss that we had to go back home so they could change their socks.

Almost no one could tell the difference between the twins, and they had a lot of fun fooling the school teachers.

Once, when Dora didn’t know the multiplication tables and was called on to recite them, Nora stood in her place and recited them. The teacher never knew the difference. I’d tell all the fairy tales to the twins. Even though the twins couldn’t talk plain, when the teacher was out of the room or busy they would tell fairy tales to the other kids.

Walking was just about the only transportation we had. Sometimes we rode in wagons. Sometimes so many of us that we couldn’t sit down and when we got to a hill, everybody except the driver, old women and babies got out and walked up the hill.

The first part of July we went to school. Every body walked and carried their lunch. A few people who lived way out in the hills came in cars. One family had twelve kids. They lived twelve miles from Flintville. All of those kids graduated from high school – 3 at a time. The second bunch of three graduated with me. Henerietta Benson lived six miles away and she walked. She stayed with us a whole lot, but she was determined to graduate and she did.

The teachers were paid $50.00 a month and the principal got $60.00. At my fifty year class reunion, one of the high school teachers was there. She said that she was getting paid $60.00 a month when she retired after teaching for fifty years. During the depression years, she got paid $30.00 a month.

School hours were from eight o’clock until four o’clock. The teachers were there when we got there in the morning and they stayed after we left in the afternoon. I hope that the other fourteen members of my class were smarter than me, for I know that no one ever got a high school diploma knowing as little as I did. Oh, I could read all right and I guess that is why I made A’s and B’s—and of-course I was always present.

We had to have a foreign language to graduate, and Latin was it. Two years of it! When I was a junior I had to have geometry and the principal, Mr. Wall, was our geometry teacher. Mr. Wall was elected County School Superintendent and took office in November, so we had to have a new principal and geometry teacher. His name was Earl Gray. He was a tall, stupid man from Texas. The first day he taught, he asked us what we knew about geometry. We told him that we knew nothing, and he said, “Well, I don’t either, so this is what we’ll do. Each of you are going to buy a workbook and you will work from that.” So we did, and therefore, I know that none of us came out of that class knowing a circle from a square.

I was black-balled by Mr. Wall, the principal, when I was in the tenth grade. Mary Will and I had algebra as the first class of the day, and Mr. Wall was our teacher. One Monday morning Mary Will didn’t go to school and Mr. Wall said, “Well, well! How are you Miss Weir?”

I said, “Fine.” He asked, “And where is the other Miss Weir?”

I said, “She’s home.” He said, “And I suppose she went to the Sunday School Social last night.”

“As a matter of fact, she did”, I answered.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with parents,” he said sarcastically. “I don’t suppose she’d know how to act if she went to a party.”

I said, “Oh yes she does for we’re not Tennessee Hill-Billies.” (He was). He drew back the yard stick to hit me. There were repairs being done to the school and a two by four had been left by my seat. I reached down and picked up the two by four and stood up. He looked at me and told me to go to my homeroom seat and stay there until he gave me permission to leave. When I didn’t go to Latin class, the teacher sent someone to get me. I told them to tell her that I couldn’t leave my seat and Mr. Wall said that I was a smart-alack.

I went to Algebra class every day, but Mr. Wall wouldn’t take my homework and pretended that I wasn’t there. The Seniors told me that he had told them that I was black-balled and that I might as well quit school because I would never get a diploma in Tennessee. But about three months later as I was going out the front door one day, he shut one door and stood in front of the other to block my way. He put out a hand and said, “Louisa, let’s be friends.”

I said, “I’ve always been friends.” He said that he shouldn’t have said what he had said, and I told him that I was sorry that I’d said what I did about Hill-Billies. Later, I found out that his son was not invited to that party (I didn’t go), and it was next door to him. I guess that is what he was mad about. But, Mr. Wall and I were good friends, even after he became Superintendent of Schools.

I graduated May 28, 1932, and a year later the school burned down. They built a new school with separate buildings for grade school and high school. They also had more teachers then. Now, Lincoln County has a co-op high school at Fayetteville, the County seat. Schools have always been very good in Tennessee, and since 1925 even the high schools have been free and all books furnished by the school system. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The year that the twins started to school there were six Weirs in school. There were also five other sets of twins in Flintville that year. There were between 300 and 350 kids in school from the first through twelfth grades. There was one teacher for each class through eighth grade and three high school teachers and between 25 and 30 students in each class. The principal taught classes and coached the foot-ball team. The ninth grade teacher coached the basket-ball team. We had a good football team, and later, the basketball team was extra good.

I remember that after we moved to Tennessee, we would take gunny sacks, tubs, or whatever we could find and go in the wagon, nutting. We would get mostly chestnuts. But there were a lot of different kinds of hickory nuts and we would get some of those also. We’d make a day trip out of it. Riley, Lillian, Mama, Papa—I guess all of the kids. Sometimes we’d go in the wagon blackberry picking too. We’d have tubs of berries. Riley could really pick the blackberries!

Riley liked to go coon hunting. Papa, Comer, and Buford never did. I don’t know if you ate coons but it was supposed to be a big sport.

Once, my boy friend, Erby and his two sisters had a good coon dog and wanted me to go coon hunting. Of-course, we couldn’t keep up with the dog, but we heard him baying. Coons were generally in a tree, but this dog was baying at a hollow log.

Erby said, “I’ll have to get a stick and twist him out.” That’s what he did but we didn’t stand back and the dog didn’t even back away. Were we ever surprised when that terrible spray covered us all over! It was a skunk, not a coon at all! I don’t know why he waited to spray until he got out, but I guess that he had to be in position. We could never wear those clothes again.

Mama said, “I’m not going to say a word for I know you’ll do crazy things like that all your life.”

Fancy was Riley’s dog. She was a feist. Everywhere Riley went, Fancy went. Mr. Reynolds, who owned the grocery store, wanted to buy Fancy the first time he saw her. But you don’t sell a member of your family.

After two years in Tennessee, Riley’s dad came to move Riley and Lillian back to Alabama. He owned a big farm in Alabama. He stopped in Flintville and asked Mr. Reynolds where Riley lived. He got out to Riley’s and they were almost loaded when Mr. Reynolds came with the sheriff. Riley owed him eighteen dollars for groceries and he had put an attachment on everything Riley had: furniture, everything.

Finally, Mr. Reynolds said that if Riley would give him Fancy, he’d call it even. Riley agreed. Mr. Reynolds took the dog and Riley and them left. That night about eleven o’clock Mr. Reynolds came to the house and asked Comer if he’d call Fancy for him. He’d gone hunting and she ran off.

About three months later we got a letter from Lillian in Alabama. Fancy had got there, about half dead! I wonder how she crossed the Tennessee river. Anyway, Fancy lived to be seventeen years old.