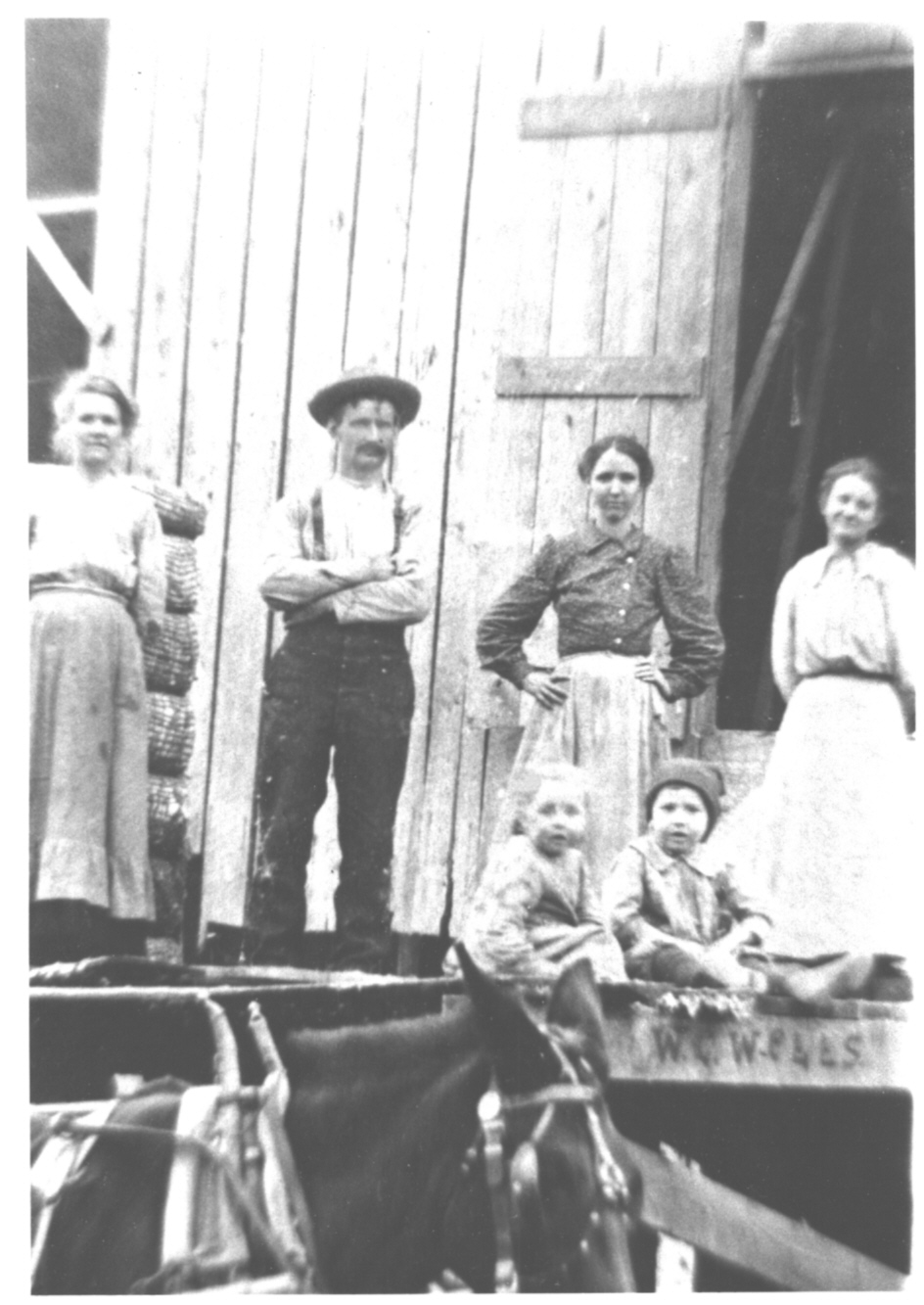

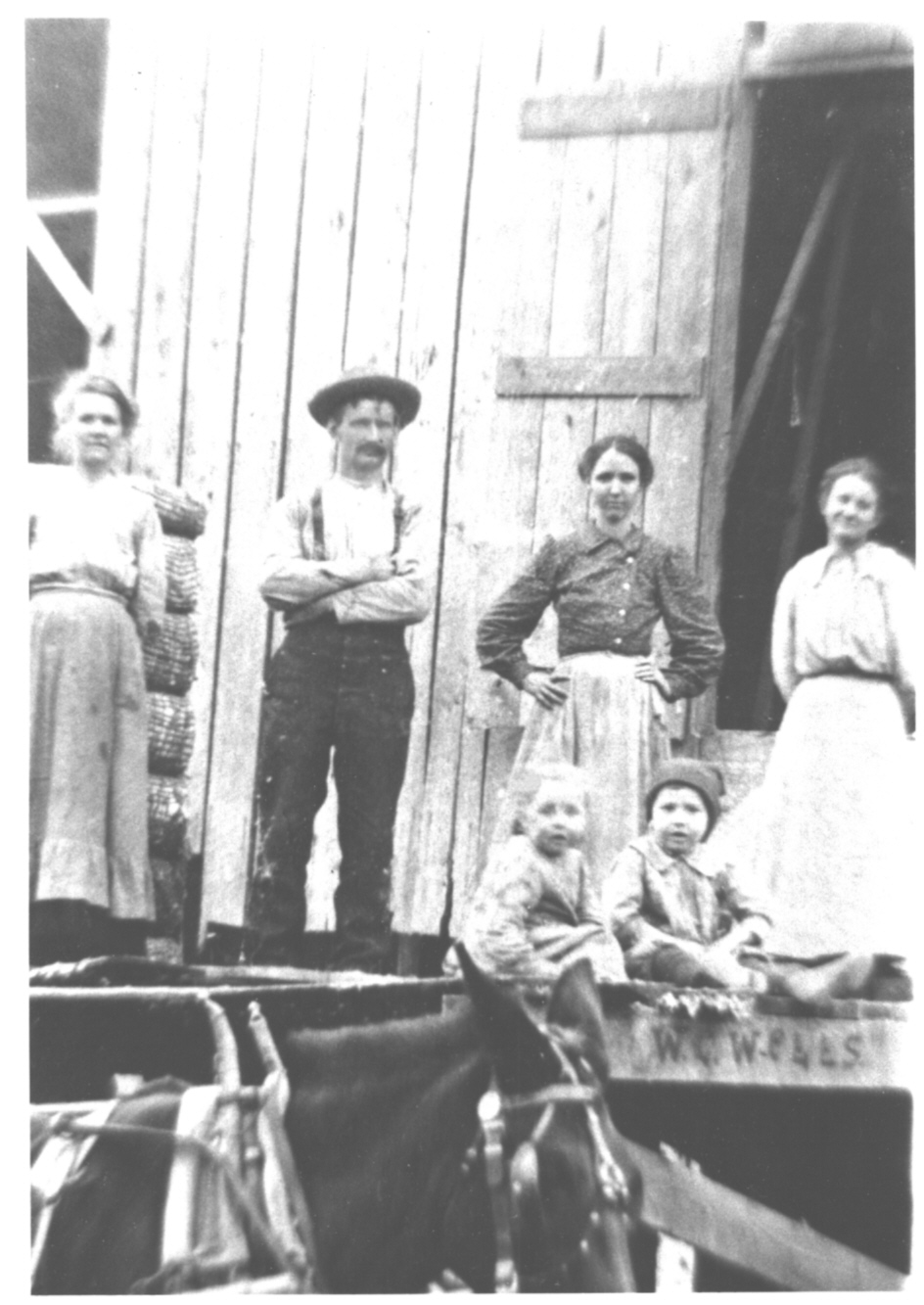

“The Cotton Gin"

Aunt

Mary Watson, Papa Willie Weir, Mama Ida Weir, Aunt Lula Wells

Lillian, and Huey Wells

The Story of my Life

Louise Virginia (Weir) Frasier

| Home | Introduction | Preface | Chapters | Do You Remember? | Stuff | Contact |

Chapter VII

My first memories are pretty sketchy. I remember having a temper tantrum and falling backwards off the bench at the dining table. Papa picked me up. Did he spank me? The next morning a big red apple was on the window sill next to my bed. Did Ruth put it there? I’m almost sure that the whole thing had something the do with Ruth. Did it?

I remember that we picked lilies with bees in them off a bush and put them in the mail box. We pinched the ends together so the bees couldn’t get out before we put them in the mail box. Who did that? I helped. Did we get spanked?

We were supposed to stay away from the cotton gin, but I remember that once we were there. We climbed up on someone’s wagon load of cotton. While they were running the suction, Comer or Buford (or both) put another boy’s straw hat up the suction. The gin ruined the hat. And once we were under the platform at the back and found some change (money).

We also used to hang around the syrup mill even though we were not supposed to. We’d eat the second skimmings although they were still pretty rank. Then we’d have to practically live in the out-house!

The syrup cane grown on Sand Mountain makes the best syrup in the Southern United States. There’s no other like it! When the cane got ripe the heads would turn brown. Then the fodder (leaves) was stripped and the seed heads cut off. The cane was cut and loaded onto the wagon. It was best to keep the stalks straight.

At the syrup mill they had presses, generally one but sometimes more depending on the size of the operation. They had mules (mostly slow lazy mules) which were hitched to the drive shaft. The cane was fed into the press by hand and then the mules went round and round like a tread mill.

The press pressed the juice into great copper pails. The cooking pans were also copper. The pans were laid over a long furnace or barbecue pit fired with wood. The pails were dumped into the first pan. When the pan got full, the furnace was fired. This was never at high heat. Everything was slow and easy. If it got too hot, it would ruin it—make it turn to sugar too soon.

After the sap came to a rolling boil, the skimmers went to work. Skimmers were men with long handled screen dippers. The sap was stirred and all the green skimmings were taken off. These skimmings were put into a deep hole in the ground at once for they would make anybody or anything deathly sick if they ate them.

The sap was boiled and skimmed three times. The last two skimmings could be

eaten and we kids ate them, although our parents told us not to. From the third

pan, the syrup was run into gallon buckets. That is Sand Mountain Alabama

Syrup. Nothing like it anywhere!

|

“The Cotton Gin"

Aunt

Mary Watson, Papa Willie Weir, Mama Ida Weir, Aunt Lula Wells

|

They still make syrup on Sand Mountain but of-course now everything is run by machinery and someone said that they add cane sugar to it. But it is still good. That’s the last thing that my mother ate before she died. She had been sick such a long time. But the morning before she went to the hospital the last time, she said that she would like some home made biscuits, butter and syrup. Dora made the biscuits and Mama ate two. She went back to the hospital that day and never ate another bite.

I remember that I ran away from home one day. I went to the house next door and wouldn’t go home. But the man put me in a gunny sack and carried me home.

I didn’t like my grandma Weir very much but she gave me some good advice which I’ve never forgotten. Grandma Weir died in 1931.

Grandma Weir told me that unless something was completely broken, don’t fix it. Always put your coffee grounds down the kitchen sink and you’ll never have a clogged drain. When you go to the apple barrel or potato bin always pick out the biggest, smoothest, soundest ones you can find. That way you’ll get to eat some nice ones, but if you try to use the culls first you’ll never get to eat a good one for the best ones will be bad by the time you get to them. And she told me “Not only do you reap what you sow, but you sow what you reap.” At first glance it seems the same but it’s different if you really think about it. I’ve always taken her advice about the coffee grounds and never had a clogged drain. And I have always picked the best potatoes or fruit first.

I remember that Grandma Weir still lived almost in front of us across the road. She had a barrel of sour kraut in her basement. Uncle Willie Wells lived in the next house down on the same side of the road. Their house was nicer and had a nice well house and a room for Low in the well house. They had a mulberry tree and Grandma yelled at us for eating mulberries. She said that they were filthy and were full of worms.

And I remember that Mary Will and I took piano lessons and practiced on an organ. The organ that we practiced on was in the parlor where the shades were down and big old pictures of our dead grand-parents were on the wall. If I’d had any talent, practicing in a dark room with ghosts watching from the walls would have scared it out of me!

--- Snatches of memories --- I remember sitting on the second stair step, Buford on the third, and Mary Will in a small rocker at the foot of the stairs—waiting for Santa Clause! I woke up in bed. I guess Santa put us to bed!

I remember putting a worm on a bent straight pin and catching minnows.

So many things you remember just snatches of, can’t get the whole picture. I remember Buford climbing on the churn to get to the clock. The churn turned over and spilled the milk. Buford got Mama’s wedding band out of the clock, put it on his finger and the ring had to be sawed off.

I remember making pitch tar out of pine knots. I remember falling out of the chestnut tree and breaking both arms. There were hundreds of spreading chestnut trees in the mountains and hills of the southern states. But in 1930 or 31 a blight hit and killed all of them. Hoyt said that you can find a few young trees in the Smokies now, but when they get about five years old, they die.

Anyway, I climbed the chestnut tree and shook the limbs so the nuts would fall from the burr. I’d been to the top and shaken them all as I came down. Mary Will and a boy were picking them up. The lowest limb was about twenty feet from the ground. Can you shinny a tree? That is without a ladder or limbs to climb on? I’d like to just be able to climb a tree again!

When I started down, Mary Will said, “There is a lot on that bottom limb.” The limb was so big that the only way I could shake it was to hold to the one above and walk out toward the end where it was smaller. That’s what I did. The limb broke and I hit a hard-packed woods road and my side hit a stump.

Dr. Morton came and took me to his office in the buggy. I remember that I was

lying on the table and Mama called and he told her that I wasn’t hurt bad—only

two broken arms, three broken ribs, and a bitten tongue. He said he’d keep me

there all night, but I cried so Comer and Buford came and got me in the wagon.

Papa was away from home working at a gin. He only came home week-ends.

|

Aunt Matt and Joe Watson |

Aunt Matt, Mama’s half sister, lived with us at various times. Once when she lived with us, Uncle Joe Watson courted her, and later, she married him. While they were courting he came to see her in a one horse spring wagon. She built a fire in the dining room fireplace and dared any of us to be near.

Do you remember, Buford? You and I got behind the dish safe which was catty-cornered making a hole behind it.

First Joe said, “I brought you something, Mattie.” He reached into his pocket and took out a bag of gum drops. They each took one, then he said, “I brought you something else, too.” And took out a pair of black stockings.

She heard us giggling and said, “Wait a minute till I get them dadburn kids out of here!” She chased us with the broom.

I remember that on Comer’s thirteenth birthday, he got his first pair of long pants. And Papa bought him and Buford a buggy and Sam. Sam was our pet for five years. And I remember that the year that Elizabeth started to school there were six Weirs in school. I suppose it was 24-25 or maybe 25-26. We moved to Tennessee from Boaz when I was in the eighth grade.

I told you that we had a T-Model. Uncle Willie Wells had one too. Then he bought an Oldsmobile—a great big ole’ touring car. One Sunday we went home with Uncle Willie after church. After dinner, the old people were in the back yard under the grape arbor. Our cousin, Huey, who was about twelve years old, said, “Lets go for a ride, I can drive.” But we couldn’t crank the car. Huey told all of us to get in (four of us and six of them counting Low) and Low would push us down the hill and after it started Low could jump on. Huey kept the car on the road OK, but he didn’t know where the brakes were or how to stop. I remember us all waving our arms and yelling. After Papa and Uncle Willie caught up with us and got us stopped, we all said “Low made us do it!”

I remember that we rode the train several times to Anniston, Alabama to visit Mama’s sister, Cana, and her brother, Genie. Once when Buford was a few days over six, we rode the train to Anniston. Kids under six rode for free. Kids from six years old through twelve years old rode for half price. Anyway, this one time Mama didn’t buy a ticket for Buford and when the conductor came to get the tickets, she hid Buford under her skirt.

Aunt Cana Summerlin, Mama’s sister, was a prohibitionist. I just remembered that she had sons named Ulysses and John. John and Otis Daniel fought in World War I. And I just remembered who Otis Daniel was. He was the son of Mama’s sister, Mandy—Grandpa Haynie’s Mandy. Mandy married Isaac Daniel and died in childbirth.

Anyway, Aunt Cana was a prohibitionist and her sons were bootleggers and drank. Most bootleggers wouldn’t drink. Once the Anniston, Alabama Newspaper ran a piece on Aunt Cana. The sheriff said that she had broken more jugs of whiskey than anybody else in Alabama. She’d find where the stills were and get word to the sheriff. But, before the sheriff could get there, she’d take an axe and smash everything is sight.

|

John B. Haynie (on the left) and some of his kids and grandkids. Maybe Aunt Cana or Uncle Genie

|

When I was growing up in

Alabama, Mama was a society person and Papa was a deacon at Bethsada Baptist

church in Marshall county, Alabama. He was a school trustee, which I guess was

a member of the school board. He belonged to civic organizations, such as Odd

Fellows and Masons. Mary Will said that he rode with the Ku Klux Clan, but I

don’t think so. What would he have ridden? A mule? Sam? Sam was a pet, but

hardly a proper mount for a PROUD Klan member.

One Sunday we were at Whitesville Baptist church and thirteen Klan members came in while the preacher was preaching. They had robes and hoods on. I was too little to know what it was about but later Mama said that the preacher had been visiting a woman and there was a lot of talk about it. They just came in quietly and sat on the back seats.

Ku Klux Klan members are not only racists, but in the 1920’s they acted as do-gooders, warning people that they got mad at by burning crosses in their yards. Actually beating them and even tarring and feathering them. Funny thing—all the men must have been real good then for it was always the younger women, especially widows who got whipped or tarred and feathered.

Evelyn started to school during the 1926-1927 school year. That was a two-teacher school—a man and his wife. Evelyn said that the only thing she remembers when she was a kid was that she had a sore toe when she started to school and somebody stepped on it. Sad ain’t it? I guess that I was the wrong age to remember Evelyn much when she was little. But she was just over two years old when the twins were born and, naturally, twins take and get a lot of attention. But I don’t remember about them either until we moved to Tennessee.

1927 -- That was the year that George William was born and the year Ruth died. The year that Buford had his first date. The year I learned to milk. The year we moved to Tennessee.

…The year Comer fell in love. He bought her a ten cent bottle of cologne. Me and Buford changed the price tag to read one dollar instead of ten cents. That was the year that I spelled down the whole school, spelling ‘sleigh’.

Mama almost died when George William was born. The doctor said that she had cancer all over her body. Ruth asked Papa what he would do with all of us kids. He said he would put us in the Odd Fellows Home in Cullman, Alabama. Ruth quit her job as dining room superintendent at Snead and got a job in the orphanage in Cullman. Ruth died two months after going there. She died of cancer of the liver. I loved her!

The times changed. The depression changed the whole world and I know that the younger girls don’t remember any of those days of long johns and surreys, etc.—the good years in Alabama. After we moved to Tennessee, there was only hard work and poverty. Comer is dead and Lillian is getting old, so it’s up to me and Buford and Mary Will to remember.

Yes, things have changed, but people are pretty much the same. There have always been and still are people who say they don’t work because they can’t find a job. And there have always been and still are people who say that anyone who really wants to work can find a job. Well, who in the hell wants to work just to be working? You have to be paid enough to pay for a place to live and to buy food and other needs. There has always been and always will be the ‘true hobos’—people who are just killing time in this lifetime until it’s time to leave this world.

Mama said that our troubles started when Papa bought the Chevrolet car. But there were other reasons. Papa wanted to go to another state where you did not have to pay tuition to go to school. With ten kids, even $10.00 each was a lot of money. Also, Papa had co-signed with some bad debtors—Uncle Willie Wells was one of them. Papa, Uncle Willie Wells, and Grandpa Weir had a cotton gin, and they were cotton brokers in a small way. They paid forty cents a pound for cotton and then the price dropped to twenty cents and they lost everything they had.

Uncle Arthur Bruce was another one of Papa’s so called friends that cheated him and made a share-cropper out of him. Papa was too gentle and trusting. But we need a lot like that today. Now every body says, “I’ve got to get him before he gets me.” In 1924 we became share-croppers.

After Uncle Willie Wells cheated Papa out of money, they moved to town and he bought the Coca-Cola bottling plant. Later he moved to Gadsdan and when he died he left the bottling plant in Gadsden to Low.

In 1927 the great depression was really getting bad. And Papa heard that in Tennessee, schools were free—even high school! He rode the train and went to Flintville, Tennessee where he rented a farm from Mr. Curry. Lillian and Riley were married then and had Junior.

Uncle Joe Watson, Aunt Matt’s husband, made some bows and fitted them on the wagon with a tarp over them. Riley, Comer, and Buford were going to Tennessee in a covered wagon! They loaded all the farm tools on the wagon and Daisy and Mary pulled with Sam trailing behind. The dogs, Ted and Fancy went with them.

Two days after they left all our household goods and Papa, Mama, Lillian, Junior, George, Dora, Nora, Evelyn, Mary Will, Elizabeth and I were loaded into three trucks and followed the boys.

There was no bridge across the Tennessee river at Guntersville, so we had to cross on the ferry. But later we learned that Sam would not get on the ferry and the boys traded him for a fool of a mare named Maude. So we lost Sam, a true friend!