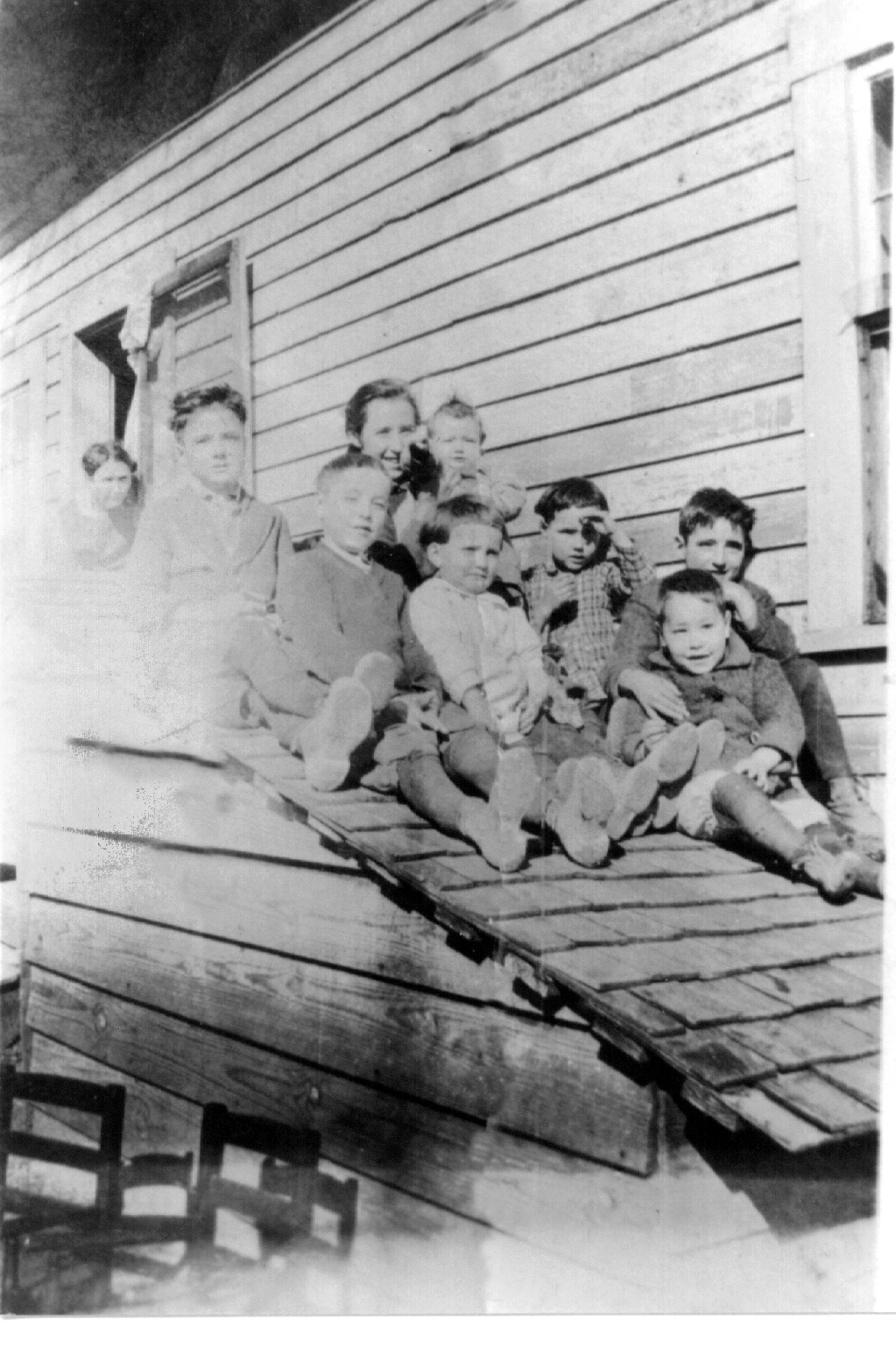

“The Cellar Door"

Mama in the window and all the kids on the door

(That's Lillian holding a baby and I think it's Mama, Louise, Shading her

eyes

and Mary Will in the white shirt)

The Story of my Life

Louise Virginia (Weir) Frasier

| Home | Introduction | Preface | Chapters | Do You Remember? | Stuff | Contact |

Chapter V

|

|

|

J |

uly 20, 1991

I talked to Virginia this morning and she said I should get each one in the family to tell all the things they remember. She said we’d probably tell you of the same things and they would be different from what the others remember. But it would still be fun. Have we let it go too long? Or are we too old to remember? Or too old to take the time to write it. Maybe Lillian and Mary Will should have a tape recorder and Buford too. Maybe all of us should have one and then get one of our kids to type it. Wouldn’t that be neat? I know I’d like to read it after it was all put together.

Probably me and Buford are the only two to remember the burning cotton. And we would tell it differently for he was the burner and I was the burnee, Ha!

And I wonder if either Buford or Lillian remembers the 4th of July. Everybody passed, going to Boaz to the picnic, but we were replanting corn—Papa too. We were mostly leaning on our hoes, watching everybody pass. Finally, Papa said if we’d get off our asses and get done, we could go too. That scared us so bad that we got done in an hour because Papa never swore.

I still remember what I wore to that picnic. I had white knee socks, black patent leather shoes, lavender organdy dress, and a flat-topped sailor hat with a lavender ribbon on it. I pushed Carl Martin into the spring at Boaz for calling me sweetheart and telling me that salt would dry up my blood. All of us kids were eating the salty ice out of the five-gallon ice cream makers. But he grabbed me and I fell in too.

That wasn’t the only time I beat up on him. Once, we had an Easter egg hunt in our yard. He kept finding eggs and showing them to me. I told him not to do that. Finally I knocked him down and was really beating him and Buford and Comer pulled me off him.

I remember another fight too. It almost turned into a feud. This was at Whitesville school in Alabama. This girl named Maggie Davis was two times as big as me. She picked on me, kept calling me “teachers lackey” (teachers pet). I asked her not to call me that.

Finally, one day after she had some other girls calling me that, she wanted me to fight her (to make her stop). I told her that I would fight her at the creek, going home after school. She had an older sister and two big old rough louts of brothers. They were all waiting when I got there; but Lillian, Comer, Buford, Mary Will, Elizabeth, and I all walked together. She almost killed me and the others fought too. Then when we got home, her mom and dad came and wanted to fight Mama and Papa -- and Papa wasn’t even home. But it was after that that Papa bought a pistol for Mama. She was afraid to shoot it but did shoot once through the door at someone.

We lived in the Garret house when Papa got the Chevrolet. It had more parts than the T-Model and never ran as well as the T-Model. Maybe that’s the reason I’ve always liked the cars Ford makes.

I guess that every kid that’s ever lived on a farm has told this story, just the what and where is different. Papa decided that he would replant the corn spaces (where the corn hadn’t come up) with white crowder peas. White crowder peas were quite expensive.

A rail road company had started to build a rail road across our farm. We got tired. We turned over a big rock in the rail road cut, poured a peck of pea seed in the hole, and rolled the rock back over the seed. Peas will sprout in three days.

Every Sunday after church, all good farmers walked over the farm to see what would need to be done the next week. Neighbors would walk together from farm to farm. That Sunday Papa came back and called all of us together.

“We have the finest pea patch around that rock in the rail road cut I ever saw. I wonder how it got there,” Papa said. Of-course the seeds had sprouted and were growing all around that rock! But Papa had done the same thing when he was young so he didn’t even fuss at us.

Mary Will reminded me about a time when she, Elizabeth, and I went to cut brush-brooms. Most yards, especially kitchen yards, were bare and packed as hard as bricks. We’d cut dogwood branches and tie them together to sweep the yard with. ad a bull that was so mean that men were afraid of him. He was not kept in the regular corral, but in a pen of his own. We were going across the pasture and I guess somebody had left the gate unlatched. Anyway, here came the bull charging right at us! new that we couldn’t outrun him and we were too scared to run anyway. A tree had blown over and was leaning on another tree and when the bull almost reached us we climbed it. We pushed Elizabeth up first, then Mary Will and finally I climbed up. The bull was right there, madder than a hornet! The tree we were on fell! It scared the bull so bad that he went meek as a lamb back to his pen and he wouldn’t even come out for two or three weeks.

Once, Comer and Buford had cleaned the stables and were putting compost in the wagon and then throwing it with shovels under the apple trees. Of-course I was with them. There was a limb about twenty feet off the ground. They told me to see if I could reach it. I reached up and took hold of the limb. They drove the wagon from under me and left me hanging twenty feet in the air. Fortunately, the ground had been plowed and was soft.

Papa kept his chewing tobacco, ‘Red Mule’, in the sewing machine drawer. I would lean against the sewing machine and smell the tobacco and it smelled so good! I guess that Papa saw me for, one Sunday, we were on the front porch and he was reading the paper. He cut a chew of tobacco, saw me smelling it, and ask if I wanted a chew. I said, “Yes, Sir”, and he cut off a big chew for me. I put it in my mouth and he said, “You’d better sit down to chew it.” That’s the last thing I remember until I woke up laying on the porch and everything was green. I still like to smell that chewing tobacco.

|

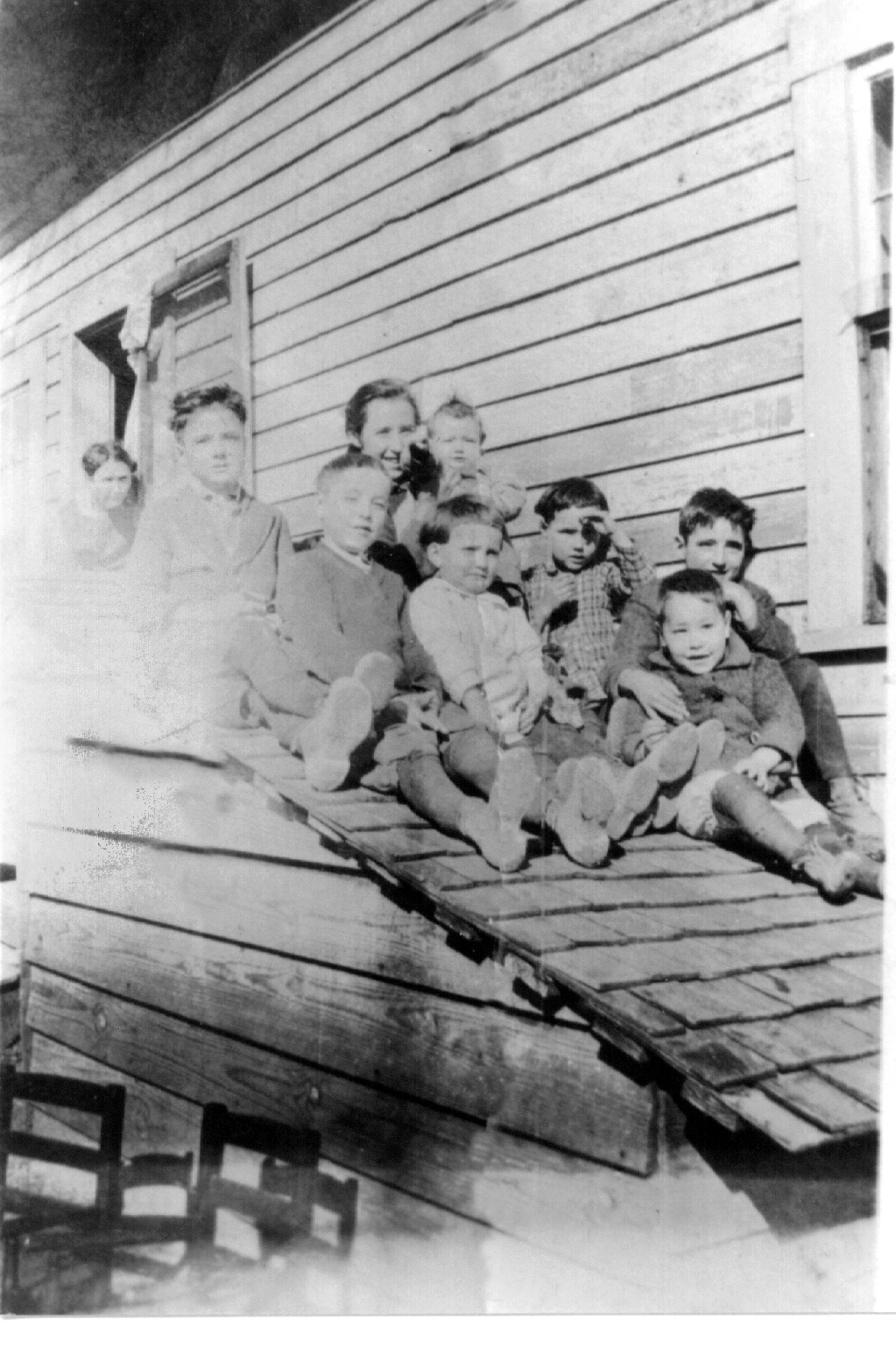

“The Cellar Door"

Mama in the window and all the kids on the door and Mary Will in the white shirt)

|

Buford smoked a cigar once. He was sitting on a tree that had blown over. He turned green as grass. He also drank once and when he came in the back door he saw a red devil sitting on the stove. That did him! I think Comer was as good a brother and man as Buford, but he didn’t go to church as much.

I remember going shopping with Mama in the buggy. There was one Jew in Boaz who had a store. He had a silk blouse that Mama wanted really bad. She went back almost every day for two weeks, but he never did go down on the price.

We wore long johns in winter and over them we wore flannel slips with long sleeves. Then we generally wore two cotton sleeveless slips over that. We wore black bloomers which bloused over the knee, black stockings for every day and white stockings for Sunday, wool dresses, and high top shoes. The long johns would get stretched and we would have to pull the black stockings over them and the elastic in the bloomers was supposed to hold the stockings up, but it didn’t do too good a job of it. Our legs must have looked terrible. Of-course the dress hems were below our knees and stood out. We had only cotton, linen, wool, and silk fabrics.

|

“The Buggy and Sam" Comer, Buford, Dora and Nora

|

If boys didn’t wear overalls (and they never did when they went out in public, even to school), they wore knickers. Knickers were shorts that went half way down their leg and then bloused like the bloomers did. They also wore black stockings. When the boys were thirteen or fourteen they got their first long pants.

The first of May everybody shed their long johns and wore union suits. Union suits for the girls are called teddies today. The ones the boys wore were really short long johns— one piece union suits without legs or sleeves. We also got lighter shoes in May and patent leather, low-top shoes for Sunday.

The second Sunday in May was Decoration day at Bethsada and Beaulah churches. Decoration day is a kind of reunion time when the families of the people buried at the cemetery get together and clean the cemetery and put flowers on the graves. We would all wear our new patent leather shoes, new clothes, and new hats. Some times we would have to wear our old ratty coats because it was so cold.

We had people buried at both churches so we would go to one church until dinner and then go to the other. We would eat ‘dinner on the ground’ at Bethsada one year and then eat at Beaulah the next year.

One year on the third Sunday we went to a church that we didn’t generally go to. I don’t remember where or even why we went. We went in a surrey, which is a two seated buggy. Those new patent leather shoes were killing me! Mama would have killed me if I’d pulled them off. She finally said that I could go sit in the surrey. A distant cousin—I don’t remember her name, they came up from Birmingham—came and sat in the surrey with me. She still had on her old heavy winter shoes. She swapped her shoes for my slippers. I was so happy to get rid of those shoes! But Mama wasn’t too happy and when we went to look for the people they were gone. She said that I’d have to wear the heavy shoes, which meant that I couldn’t go very many places that summer for she would be ashamed of me. But Ruth gave me a pair of white patent leather shoes and a black pair too. Mama never let us go barefoot in public. She didn’t let us go barefoot at all until the first of May.

All the women had long hair in the nineteen teens and twenties. But in 1925 the flappers appeared. They bobbed their hair and wore short dresses and stopped wearing corsets and long skirts. Flat chests were preferred so bands were worn tight around the chest to flatten the breasts. Women wore tight hats -- that is hats like caps with no brims. They pinned them through the hair with long hat pins

Lillian wanted me to tell about her being a flapper. But Mama sure didn’t give her much chance for flapping! – although she did wear the short skirt-like dresses with fringe and the brimless hats that fit the head like a glove. Sometimes they would have a big flower over the right ear, but most were plain. You wore slippers with these dresses. High top shoes were out.

Mama wouldn’t let Lillian do the Charleston—but of-course she did. And once, she and three friends of hers got some lip rouge and put it on. Before that, they’d rub wet red tissue paper on their lips and cheeks. This time they used the lip rouge. There were no lipsticks—they didn’t know how to put anything in tubes yet.

This lip rouge was advertised as ‘Kiss Proof’. As it turned out it was also water proof. Them girls rubbed their lips sore, but the rouge was still there. One girl’s father whipped her. At first, Mama didn’t notice Lillian. But I was mad because Lillian wouldn’t let me use the lip rouge (Lillian said) so I told Mama that she put some of that old lip rouge on. “Tattle tale.” I didn’t remember that I was a tattle tale but I guess everybody is. Lillian also said she whipped me with a switch several times—that is, when she could catch me!

Anyway, during the twenties women actually stopped wearing hats at all. Before the twenties, hats were the most important item a woman owned. Milliners, or hat makers really made good money.

Every town had a millinery or hat shop. Women’s hats were the big item. You should have seen some of those hats: bird nests with eggs and bird, whole bowls of vegetables, feathers two feet tall. You’d wonder why they didn’t fall off. But women had hat pins about ten inches long and they would stick them through the hat and into their bun of hair. Women’s hats were the most expensive things in the 1906 Sears Catalog. The only thing that cost more were prefab houses. You could buy a full length mink coat or a full carat diamond ring cheaper than you could get some women’s hats.

|

“The Hat” Aunt Nan Collier (Mama Was never too clear who she was. Mama's grandmother, Sarah E. Brasher has a sister, Nancy but she died in 1914.)

|

Nobody seems to want to remember it like it was. When I was younger, I was always able to laugh at myself, but never at others. I have a lazy eye making me have funny eyes and from the time I can remember, people called me “that cross-eyed Weir girl.” Curiously enough, it was the teachers and adults who called me that. No kids ever called me cross-eyed. I know that I was a very homely kid and a tomboy too. I had no personality at all. I should have had a very serious problem with my ego, but I don’t think I ever did. I just accepted that I was ugly and went with it.

So I remember the happy good things more than I remember the poverty. Papa was not too old when he died but I know he was ready to die. He did the best he could. I wonder if I have? I say I’ve always done the best that I could at the time. But I’m not sure, when I look back, it doesn’t seem like I was a good mother and I think that I must have been a terrible wife. I’ve always kept myself away from things that I can’t change. Maybe if I’d been a different kind of person, I could have changed things some. I never worked outside the home because H.N. did not want me to—and since I’ve always been lazy, it suited me.